Python

Python Links

- Python

- Python Wikipedia

- Python IDE list

- Python 3 FAQ

- Galileo Computing Openbook Python

- Python 3: Das umfassende Handbuch (Galileo Computing)

- Python tutorial"

print("a", "b", "c", sep=":", end=".", file="myfile") #a:b:c.

Python interactive mode

Python 3.2.3 (default, Jul 23 2012, 16:48:24)

[GCC 4.5.3] on cygwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> 21 * 2

42

Data types

Python build in basic data types

int

In Python int has no fixed upper or lower bounds. Therefor there is no long type.

Strings

See also Python 3 String

s.count("o")

# 2

s="xxx yyy zzz:fff:ggg:zzz,ttt"

print(s.split(" ")) #['xxx', 'yyy', 'zzz:fff:ggg:zzz,ttt']

print(s.split(" ",1 )) #['xxx', 'yyy zzz:fff:ggg:zzz,ttt']

print(s.partition(" ")) #('xxx', ' ', 'yyy zzz:fff:ggg:zzz,ttt')

s.find("zzz") # 8

s.index("zzz") # 8

s.find("no-no") # -1

"The price is {price:.2f} {currency}".format(price=42, currency="EUR") # The price is 42.00 EUR

Strings are treated similar to lists.

print(3 * "x") # xxx

s="John Doe"

print(len(s)) # 8

print(s[0]) # J

print(s[-1]) # e

print(s[1:3]) # oh

print(s[5:]) # Doe

print("0123456789"[0:11:2]) # 02468

print(s[::-1]) # eoD nhoJ

print(s.index("D")) # 5

print(s.count("o")) # 2

Strings spanning more than one line

strInMultipleLines=("Hello "

"World")

print(strInMultipleLines) # Hello World

strWithLineBreak="""Hello

World"""

print(strWithLineBreak) # Hello

World

Bytes Bytearray

While a Str may contain Unicode characters which need more than one byte, Bytes and Bytearray represent data represented by bytes. Bytes is immutable, Bytearray is mutable.

myBytearray=bytearray(myBytes)

Code file encoding declaration

Put this in the first line of every code file to declare its file encoding

Lists

myList.sort()

print(myList) # [1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8]

if(5 in myList):

print("We got a 5")

myList[2:4] # 5, 6

myList[:] # [1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8]

myList[-1] # 8 the first element, count backwards

myList[0:5:2] # 1, 5, 7 (every second element in the range [0:5]9

len(myList) # 6

max(myList) # 8

min(myList) # 1

myList.index(6, 0, 5)) # 3 (the first position of a 6 in the range [0:5]

myList2=[42]; # [42]

myList2.append(13); # [42, 13]

#myList2.extend(12); # error, TypeError: 'int' object is not iterable

myList2.append('Hello'); # [42, 13, 'Hello']

myList2.extend('abc'); # [42, 13, 'Hello', 'a', 'b', 'c'] Maybe not want you want

myList2.append([1,2,3]); # [42, 13, 'Hello', 'a', 'b', 'c', [1, 2, 3]] Maybe not want you want

myList2.extend([4,5,6]); # [42, 13, 'Hello', 'a', 'b', 'c', [1, 2, 3], 4, 5, 6]

Double-Ended Queue

Adding elements in front of a list is expensive, consider a double-ended queue instead:

q=collections.deque()

l.append(i) # 0.013 seconds for 20000 calls

l.insert(0, i) # 14.272 seconds for 20000 calls

q.append(i) # 0.011 seconds for 20000 calls

q.append_left(i) # 0.011 seconds for 20000 calls

Those queue may even have a max length after which the last (or first) element is dropped if you add new elements at the front (or end)

Tuple

Read only lists, faster

myTuple[4]=2 # TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

But avoid a Tuple if you want to add many elements to it later on. Adding an element to a Tuple is much slower than adding one to a list.

Slicing

The [] syntax may be used to get a true copy of a list

myListCopyB=myList[:] # get a subrange of myList from the smallest to the biggest element (everything). This creates a true copy

(myListCopyA==myList and myListCopyB==myList) # True, both have the same values

(myListCopyA is myList) # True, same object

(myListCopyB is myList) # For mutable objects this will be false, different objects

copy

Create a copy of an object (instead of a new reference to the same object).

a=copy.copy(f)

b=copy.deepcopy(f)

Hashmap Dict

33: "John",

1: "Frank",

4: "Jane",

17: "Claire"

}

myDict[4] # Jane

del myDict[17]

myDict[17] # KeyError: 17

myDict.get(17, "Unknown") # Unknown

for myKey in myDict:

print(myKey) # 33, 4, 1

for myValue in myDict.values():

print(myValue) # John, Jane, Frank

for myKeyValuePair in myDict.items():

print(myKeyValuePair) # (33, 'John') ...

if 33 in myDict:

pass

Object where you can iterate over (like a Dict) can be sorted via

This would not work as a dict does not provide its elements in an order

This container has an order for all elements in it

Collections.Counter

All unknown keys are initialised with 0 the first time you access them

cnt=collections.Counter()

print(cnt['Foo']) # 0

s="Hello World"

for k in s:

cnt[k]+=1

print(cnt) # Counter({'l': 3, 'o': 2, 'r': 1, 'e': 1, 'W': 1, 'H': 1, 'd': 1, ' ': 1})

cnt2=collections.Counter(s) # if iterable it k

print(cnt2) #Counter({'l': 3, 'o': 2, 'd': 1, 'r': 1, 'W': 1, ' ': 1, 'H': 1, 'e': 1})

print(cnt2.most_common(2)) # [('l', 3), ('o', 2)]

Collections.defaultdict

Similar to collections.Counter, but with a defaultdict you can initialise new key values by yourself

character2posList=collections.defaultdict(list)

s="Hello World"

for i in range(0, len(s)):

character2posList[s[i]].append(i)

print(character2posList) # {'H': [0], 'e': [1], 'l': [2, 3, 9], 'r': [8], 'd': [10], 'W': [6], ' ': [5], 'o': [4, 7]}

Set frozenset

mySet=set(("A", "B", "A", "C")) # {'B', 'C', 'A'}

mySet={'B', 'C', 'A'} # {'B', 'C', 'A'}

thisIsNoEmtpySet={}

type(thisIsNoEmtpySet) # <class 'dict'>

mySet=frozenset({"A", "B", "A", "C"}) # frozenset({'A', 'C', 'B'})

mySet.add("X") # AttributeError: 'frozenset' object has no attribute 'add'

None

There is only one instance of the type None, which has the value None (similar to null in other languages). As there is only one instance of None use the is operator instead of the == operator to test for it (faster)

...

if searchResult is None:

print("Nothing found")

Complex numbers

Casting

print ( float(42) ) # 42.0

print ( bool(0) ) # False

print ( bool(1) ) # True

print ( bool(2) ) # True

print ( complex(42)) # (42+0j)

print ( complex(42,2))# (42+2j)

x="-"+str(42)

Variables in General

Variables do not have a fixed type, may change during runtime, variable names are case sensitive. Do not use any of those Python reserved words.

b = 2

a * b

# 16

In Python a variable name is a reference to an address in the memory.

b=a

c=[1,2]

With the == operator you can test if two references point to the same value.

# True

This does also work if you compare a float to an integer value but for example not if you compare a string value to an Integer value. In Java the == operator would test if two references point to the same object / the same address in memory. If you need the Java behavior in Python you can use the id method or the is operator

print(a is b) # True

print(id(b)==id(c)) # False

Python may try to save memory by merging two objects which are immutable into one if they have the same value

b=5

print(a is b) # Likely to be true

You can also enforce that all references to a variable are freed to help the garbage collector. If you try to use such a variable afterwards you’ll get an error.

Operators

Standard operators

-

/

//

*

** (power of)

% (modulo)

In Python if you divide two Integers you always get the not rounded result (not like Java or C). With the // operator you will get an int result

# 2.5

5 // 2

# 2

Logic Expressions

>

<=

>=

!= (same result a xor would deliver)

==

not

or

and

is

is not

in

not in

There is no increment or decrement operator in Python (x++, --xx, ...)

Combinations of logical expression are interpreted differently in comparison to e.g. Java. For example

is interpreted as

While Java would interpret the first comparison, get true of false and would then compare true of false to the next term.

Statement Bodies

Instead of using parenthesis to group a statement body to its statement, Python uses a colon and then line indention:

print ("Everythin is")

print ("ok!")

Attention: Tabs are interpreted as 8 whitespaces, so make sure your editor is configured like this!

If you do not have a statement for the body yet, you can use the

statement which does nothing.

if Statement

print ("one")

elif x==2:

print ("two")

else:

print ("something else")

There is no switch / case statement in Python. For switch statements which just assign values this is a workarround

res={

'a': 2,

'b': 2,

'Foo': 3

}.get(x, 0)

Conditional Expression

Conditional Expressions

If you have an if statement to fill a variable

grant_access="Yes"

else:

grant_access="no"

You may convert this into a one line conditional expression

enum

class Day(Enum):

Monday = 1

Tuesday = 2

Wednesday = 4

if (Day.Monday is not Day.Wednesday):

...

Loops

While Loop

Normal while loop with break (terminates the while loop completely) and continue (stops current run and starts next while loop run). You can have an else expression behind the while loop which is only executed when the while condition is no longer true (so the while loop terminated normaly)

if (i<0):

break

i=i+1

if ((i % 2)==0):

continue

print(i)

else:

print("while loop terminated normally")

For Loop

Loop to iterate over something. If you want to iterate over a range of numbers use the range expression

You can also use the break and continue statements

print (i) # 0 2 4 6 8 10

else:

print("for loop terminated normally")

Functions / Methods

Use the def keyword to define a method. In order to make an parameter optional, provide a default value

print ("Name: "+name+" age: "+age+" sex: "+sex)

When you call your function either provide the values in the same order as the parameters where defined or provide a name for each value

printPerson(sex="f", name="Jane", age="32")

printPerson("Frank", "m")

If you cannot change the original function you may use the functools to create a new one which provides default values and calls the old one

print(p1, p2, p3)

import functools

function2=functools.partial(function1, p2='planet', p3='Earth')

function1('Hello', 'planet', 'Earth') # Hello planet Earth

function2('Hello') # Hello planet Earth

A method may have a non fixed number of parameters

print(a)

print(b)

print(c)

for x in rest:

print(x)

printAllArguments(1,2,3,55,66,77) # 1,2,3,55,66,77

You can also get the extra parameters together with a parameter name

print(immediately)

if("restart" in commands):

print(commands["restart"])

if("logOff" in commands):

print(commands["logOff"])

allCommands(immediately=True, restart=True, logOff=False)

You may force the user to call all parameters by their name

print("Hi")

youHaveToNameTheParameters(parm2="x", param1="y")

If you have an object which you can iterate over, this object may be split into different parameters with the * sign

def printAll(a, b, c):

print(a)

print(b)

print(c)

Within a method you may read any global variable

myMethod()

def myMethod():

print(myID) # 42

As soon as you also try to write to a global variable it is suddenly undefined

myMethod()

def myMethod():

print(myID) # UnboundLocalError: local variable 'myID' referenced before assignment

myID=43

With the global keyword you can allow write access to one or more global variables

global myID

print(myID) #42

myID=43

myID=42

myMethod()

print(myID) # 43

Within a local method you can access variables of the outer method with the nonlocal keyword

myID=42

def innerMethod():

nonlocal myID

myID=14

innerMethod()

print(myID) # 14

In Python parameters are passed as a reference to the original object, no copy by value. This is especially a problem when you have a default parameter which is modifiable (like a list). As the default parameter is shared by all calls to the method changes may hit you in surprise

preDefinedResults.remove("OK")

myFunction() # works

myFunction() # ValueError: list.remove(x): x not in list

def myFunction2(preDefinedResults=None):

if(preDefinedResults is None): preDefinedResults=list(("OK", "Error"))

preDefinedResults.remove("OK")

myFunction2()

myFunction2()

Python build in functions

Lamda (in line) functions

Define a one line function

print("The function 5x^2 + 3x - 2 is 0 at these places:")

print(abc(True, 5,3,-2)) # -1.0

print(abc(False, 5,3,-2)) # 0.4

Filter

Define a filter function (lambda) and your data, get the filtered data back. Get all even numbers:

res=filter( lambda x: (x%2)==0, nr)

for r in res:

print(r) #0, 2, 4, ...,18

Map

The map function expects a lambda function and for each parameter of the lambda function a list (all with the same size).

res=map(addCurrency, [11.3, 42.00, 50]) # ['11.3 Eur', '42.0 Eur', '50 Eur']

addCurrency2 = lambda val, cur: str(val)+" "+cur

res=map(addCurrency2, [11.3, 42.00, 50], ['EUR', 'USD', 'GBP']) # ['11.3 EUR', '42.0 USD', '50 GBP']

Comprehensions

Build a List, a Dict or a Set from an existing data. Assume we have two lists of names

boys =['James', 'John', 'Robert']

List Comprehensions

Initialise a list with values (doing the same with a for loop would be much slower)

Get a list with all girl names

[girls[i] for i in range(len(girls))] # ['Patricia', 'Linda', 'Barbara']

Get a list with all girl names containing an 'r'

Get a list of all possible couples between girls and boys

# ['Patricia+James', 'Patricia+John', 'Patricia+Robert', 'Linda+James', 'Linda+John', 'Linda+Robert', 'Barbara+James', 'Barbara+John', 'Barbara+Robert']

Replace some values in a list (e.g. all values not larger than 5)

Dict Comprehensions

Get a dict which maps an increasing id to a girls name

Get a dict which maps a girl's name to a boy's name

You sometimes have rows containing columns and you need to know the widest entry for each column (so you can make the column wide enough). Once you have the rows with columns and know how much columns you have, this is pretty easy. This will walk through all columns for all rows and remember for each column i the widest entry.

nr_of_columns=...

{ i:max([len(str(r[i])) for r in rows]) for i in range(nr_of_columns) }

Set Comprehensions

Like List Comprehensions, but you get a Set

print({x for x in number}) # {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

Generator

For the following examples we need a method isPrime(n) to check if a number is prime. This is an inefficient example for such a method

def isPrime(n):

if(n<2): return False

if(n==2): return True

s=int(math.sqrt(n))+1

for i in range(2, s+1):

if((n%i)==0):

return False

return True

A Generator is a method which has yield statements instead of return statements and the kth call to it return the result of the kth. yield that will be reached in that method.

if(n>=2):

yield 2

i=3

while i<=n:

if(isPrime(i)):

yield i

i=i+2

This will print all prime numbers until number 43

print(x)

itertools

Extra generator functions. Example, group all elements together (if they have the "same" value and are neighbours in a your list)

n=([1.0,1.4,2.2,1.9,3.3,3.1,3.12,3.9,4.0,5.1,6.5,6.3,7.1,8])

def compareFunction(val):

return math.floor(val)

for x,y in itertools.groupby( n, compareFunction ):

print (x,list(y), sep=": ")

Result

2: [2.2]

1: [1.9]

3: [3.3, 3.1, 3.12, 3.9]

4: [4.0]

5: [5.1]

6: [6.5, 6.3]

7: [7.1]

8: [8]

Generator Expression

Like a List Expression it get all the numbers, but does not create an explicit list

Iterator

Add an inner method to your class which offers some iterator relevant methods and one can iterate step by step over your object

class PrimeNumbersIterator:

def __init__(self, maxP):

self.maxP=maxP

self.current=2

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if(self.maxP<2):

raise StopIteration

elif(self.current==2):

self.current=3

return 2

else:

while(self.current<=self.maxP):

if(isPrime(self.current)):

res=self.current

self.current+=2

return res

self.current+=2

raise StopIteration

def __init__(self, maxP):

self.outerMax=maxP

def __iter__(self):

return self.PrimeNumbersIterator(self.outerMax)

Example usage

print(i)

You can also have an object which offers random access like an array. This example offers you the possibility to get the kth prime number.

def __init__(self, maxNumberOfPrimes):

self.maxNumberOfPrimes=maxNumberOfPrimes

def __len__(self):

return self.maxNumberOfPrimes

def __getitem__(self, index):

if(index==0):

return 2

else:

# This is very inefficient!

currentTest=1

currentCounter=0

while(currentCounter<index):

currentTest+=2

while(not isPrime(currentTest)):

currentTest+=2

currentCounter+=1

return currentTest

It can be used like this:

for i in range(5):

print(i, data[i], sep=": ")

(sucks because it does not cache any values)

zip

Expects parameters with lists, builds new lists, where in list k are all the k th elements of the parameter lists

list2=list(("1", "2", "3"))

list3=list(("a", "b", "c"))

zip(list1, list2, list3) # [ ('A', '1', 'a'), ('B', '2', 'b'), ('C', '3', 'c')]

all any

You often have to check a list if any or even all entries of it fulfil some condition. Are all elements in this list True?

if all(myList):

...

Is any element in this list True?

if any(myList):

...

This is even handy when your condition is different. Assume you want to know if all numbers in a list are larger than 5. First use a List Comprehension to transform all numbers to True / False depending on their value being larger 5 or not and than the all condition

larger_five=[i>5 for i in mylist ]

if all(larger_five):

print("All entries are >5")

chr

Get the character for its code

chr(8364) #€

hash

Hash code of an object

hash("a") #3244471635557390282

pow

pow(6, 2, 5) # 1

Exception

def readMyList(position):

try:

data[position]

except IndexError as e:

print("IndexError", e.args, sep=", ")

except (AssertionError, MemoryError) as e:

print("Ok, that was unexpected")

raise RuntimeError("Oh oh!") from e

except e:

print("Some other exception found", e)

# raise the exception as it is

raise

else:

print("Everything went ok")

finally:

print("Bye bye")

readMyList(2) # Everything went ok, Bye bye

readMyList(4) # IndexError, ('list index out of range',) Bye bye

Assert

You can add assert statements to your code to find programming errors. They are only checked during development (if __debug__ is True)

assert((1+1)==2)

assert((1+1)==3) #

Use

to skip them.

Classes

Python classes Python magic functions

Please note, that you are not supposed to use Getter and Setter Methods in Python like you would for example do in Java. So all your class attributes are public and can be used directly

def __init__(self, pAge):

self.age=pAge;

p1=Person(42)

p1.age=p1.age+1

print(p1.age) # 43

The advantage of this is of course that you do not have to create or even write also those Getters and Setters which just do nothing than passing the value 1:1 through. If you change your mind later and really want to control or change the values when they are set or accessed you can implement it like this:

def __init__(self, pAge):

# this will now call the method with the @age.setter Annotation

self.age=pAge;

@property

def age(self):

print('Somebody access the value of age : '+str(self.__age))

return self.__age

@age.setter

def age(self, pAge):

print('Somebody stores a new value for age: '+str(pAge))

self.__age=pAge if pAge>=0 else None

For your clients nothing changes in the interface

p1.age=p1.age+1 # Somebody access the value of age : 42 Somebody stores a new value for age: 43

But internally you can control what is happening to the values. This is achieved by redirecting all read or write access to age to the two helper functions which store and read the value in the __age variable. Variables starting with _ are by convention private in Python (but that is not enforces). Variables starting with __ cannot been accessed in Python outside the class without tricks.

Instead of using the Annotations to define a Getter or Setter like method in Python, you can also use this

and provide a getter Method with the name "getAge" and a setter method with the name "setAge".

Another class example, a Set class which extends a collection class

''' A small demonstration class for a simple container '''

# limit the attributes to these:

__slots__=("data")

def __init__(self):

''' Constructor '''

self.data=list()

def add(self, newEntry):

self.data.append(newEntry)

def remove(self, entry):

self.remove(entry)

def contains(self, entry):

return(entry in self.data)

@staticmethod

def StringWithAllEntries(data):

res="("

for d in data:

res+=" "+str(d)

res+=" )"

return res

def __str__(self):

''' toString method '''

return MyContainer.StringWithAllEntries(self.data)

class MySet(MyContainer):

''' A small Set container '''

def __init__(self):

MyContainer.__init__(self)

def add(self, newEntry):

if(not self.contains(newEntry)):

MyContainer.add(self, newEntry)

def __str__(self):

return MyContainer.__str__(self)

st=MySet()

st.add(1); st.add(5); st.add(9); st.add(5)

print(str(st))

Class example, a length with a unit. You may add or compare two objects of this class, even if they have a different unit.

class Distance:

normalUnit="m"

supportedUnits={"m": 1, "km": 1000, "mm": 0.001,

"mi": 1.482, "yd": 0.9144, "ft": 0.3048, "in": 0.0254, "sm": 1.852,

"AE": 149597870691, "Lj": 9460528000000000, "pc": 30856776000000000,

"Å": 0.0000000001, "Lp": 1.616199e-35

}

def __init__(self, pValue, pUnit):

self.value=pValue

self.unit=pUnit

def setUnit(self, unit):

if(unit in Distance.supportedUnits.keys()):

self._unit=unit

else:

raise ValueError("Your unit "+unit+"is not supported yet")

def getUnit(self):

return self._unit

unit=property(getUnit, setUnit)

def getNormal(self):

factor=Distance.supportedUnits.get(self.unit)

value=self.value*factor

return Distance(value, Distance.normalUnit)

def __eq__(self, other):

if(self.unit==other.unit):

res=(self.value==other.value)

else:

res=(self.getNormal().value==other.getNormal().value)

return res

def __hash__(self):

norm=self.getNormal()

res=hash(norm.value, norm.unit)

return res

def __add__(self, other):

if(self.unit==other.unit):

return Distance(self.value+other.value, self.unit)

else:

return Distance(self.getNormal().value+other.getNormal().value, Distance.normalUnit)

def __gt__(self, other):

if(self.unit==other.unit):

return (self.value>other.value)

else:

return (self.getNormal().value>other.getNormal().value)

def __str__(self):

res="Distance: "+str(self.value)+" "+self.unit

if(self.unit!=Distance.normalUnit):

normal=self.getNormal()

res+=" ( "+str(normal)+")"

return res

d1=Distance(999, "mm")

d2=Distance(1, "mm")

d3=Distance(1, "m")

print(d1) # Distance: 999 mm ( Distance: 0.999 m)

print(d1+d2) # Distance: 1000 mm ( Distance: 1.0 m)

print(d1+d2+d3) # Distance: 2.0 m

print(d1>d2) # True

print(d1>d3) # False

If a class provides __eq__ and one of __lt__ __gt__ __ge__ __le__ the following will provide the rest

class Foo:

Callable classes

Classes can be called like methods if the provide a method __call__

Function decorators

Callable classes can be added as function decorators to functions. This may be used for example, to cache parameters and their function result

def __init__(self, function):

self.cache = {}

self.function=function

def __call__(self, parameter):

if(parameter not in self.cache):

res=self.function(parameter)

self.cache[parameter]=res

print("Calculated new value", parameter, res, sep=", ")

return res

else:

res=self.cache.get(parameter)

print("Returned cached value", parameter, res, sep=", ")

return res

Neither your method nor code using the method has to be changed to use this, just add the Function decorator

def isPrime(n):

...

You can even have more than one function decorator

@F2

@F3

def foo()

This will call

Cache the last 20 results from this function

def myfunction(n):

Closures

Imagine you have a function with expects some parameters and computes a result for them. Now your function should be able to operate in different modes. You could add another parameter to your function to indicate the mode to operate in. But maybe you do not want to pass the mode with every calculation. You could put the method into a class and store the mode in the object instance. But than you need to create object instances. Another way are Closures in Python. You have a function which just gets the mode and returns a reference to an inner function which stores internally (and invisible) the context of the external function.

# the current context connected to the internal function to which we will return a reference to below

def doIt(pValue1, pValue2):

print("Called doIt parameters "+str(pValue1), str(pValue2))

if(pCalcMode=='Add'):

return (pValue1+pValue2)

elif(pCalcMode=='Multiplication'):

return (pValue1*pValue2)

else:

return None

# return a reference to the inner function (the closure)

return doIt

So you can create different Closures

mult=calculation('Multiplication');

The “plus” Closure remembered that you want to do addition and the “mult” Closure remembered that you want a multiplication.

Now you can call the closures like normal functions

mult(2, 3) #6

Modules

A Python module is Python code which is stored in a separate file. If the file is named foo.py the module name will be foo Code in other files may use the code in the modules after it has been imported

All the code in foo can be reached by the prefix foo, e.g. foo.theirMethod(42). You may change the to be used prefix

so you will reach the code with bar.theirMethod(42) If you do not want to any prefix and have all the code of the module in your namespace use

but for larger modules, this is not recommended. You may however import single methods without the need for a prefix

from math import cos, pi

Within a module you can find out in which file you where found and what your module name is. If your module was the starting point of the program you will find the name __main__ instead in it.

if __name__ == '__main__':

# do something special

Several modules may be grouped into a package, which is a folder with one or more module files plus a file called

If you import a package instead of a module, the __init__.py file will be executed.

You can specify a relative while importing. One dot . represents the current path, each additional point (.., ...,) is one level higher

If you put the class de.tgunkel.de.example.python.Helpers.MyLogger into a file called MyLogger inside the package de.tgunkel.de.example.python.Helpers you can import it like this

otherwise you might get the error

with statement

If your Class provides an __enter__ and __exit__ method it can be used in a with statement. This is helpful if you need code to be executed when you enter the with block and when you leave it again. Example

def __init__(self, todoName):

""" Normal constructor """

self.todos=""

self.todoName=todoName

def __enter__(self):

""" Called when the with block is entered """

print("You can now add your tasks for "+self.todoName)

return self

def __exit__(self, exceptionType, exceptionValue, execptionTraceback):

""" Called when the with block is left, either normally or through an exception """

if(exceptionValue==None):

print(self.todoName+" Do not forget: "+self.todos)

else:

print("We got an exception of type "+str(exceptionType))

# do not throw the exception again

return True

def addTODO(self, todo):

self.todos+=todo+", "

Normal usage

t1.addTODO("Laundry")

t1.addTODO("Clean room")

We get an exception

t1.addTODO("Shopping")

raise IndexError()

This is often used for IO related code, where you have to close your connections no matter why you stop the IO.

File Read Write Input Output

Python file open Read from a file

try:

for line in f:

line=line.strip()

print(line)

finally:

f.close()

The with statement will automatically close the file

for line in f:

line=line.strip()

print(line)

Write into a file

f.write("Hello world")

f.close()

CSV read and write

with open(pURL, encoding="utf-8") as f:

mycsvreader=csv.reader(f, delimiter=';', quotechar='"')

for line in mycsvreader:

for cell in line:

print(cell);

Docstring Documentation

Similar to JavaDoc

''' A demo class

@author: Thorsten Gunkel

@contact: tgunkel-lists@tgunkel.de

@copyright: Thorsten Gunkel

@license: GPL3

@organization: No Organization inc.

@see: http://docs.python.org/3.3/library/functions.html#pow

@since: Version 1.0

@warning: This is only a demonstration object

@attention: This is only a demonstration object

@note: Enjoy yourself

@requires: Good luck

@version: 1.0

@change: 2013-06-10: Nothing changed

@todo: Test it

@bug: #1234 Sucks!

'''

@staticmethod

def myPow(base, exp):

'''

@param base: The base

@type base: int

@param exp: The exp

@param exp: int

@raise FancyException: The may actually never raise a FancyException

@return: base^(exp)

@rtype: int

@deprecated: Use Pythons pow method instead

'''

return base**exp

In Eclipse you can press CTRL 1 on a method name to generate a docstring template.

In your code the documentation can be read via

and in the interactive mode via

Tests

You can either specify test cases and their to be expected results in the method comments

def iterSqrt(number, steps=100):

"""

This method estimates to sqrt of your number via the Heron algorithm

@param number: The number we should build the sqrt of

@param steps: Optional parameter to specifiy how many iterations we should calculate

@return: Something near the value of sqrt(number) or None when number is < 0

>>> iterSqrt(4)

2.0

>>> iterSqrt(9)

3.0

>>> iterSqrt(-1)

>>> iterSqrt(9, 0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

IndexError: We need at least one step to calculate a value

"""

if steps<1: raise IndexError("We need at least one step to calculate a value")

if number<0: return None

else:

res=(number+1.0)/2.0

for i in range(0, steps):

res=(res+number/res)/2.0

return res

doctest.testmod()

Usually you will spread your code over different files (called modules in Python) and classes within those modules. Normally doctest.testmod() only checks for tests in the main module. This is how you can start tests for other modules

import de.tgunkel.pythondemo

doctest.testmod(de.tgunkel.pythondemo, verbose=False, extraglobs={'t': de.tgunkel.pythondemo.MyFirstClass()})

This will check all comments in the specified file. Also an object instance of the class MyFirstClass (called t) is passed to all tests so you can write something like

11

You can also get an overview how many of your tests failed

If at least one tests fails you might even stop before the actual program starts

raise RuntimeError("We stop if at least one test failed "+str(fails)+"/"+str(tests))

If you accidentally pass a class instead of a module name you get this error message

TypeError: testmod: module required; <class 'de.tgunkel.pythondemo.MyFirstClass'>

You can also specify JUnit like test cases in Python

import math

class IterSqrtTest(unittest.TestCase):

def testSquareNumbers(self):

self.assertEqual(iterSqrt(4), 2)

self.assertEqual(iterSqrt(9), 3)

self.assertEqual(iterSqrt(16), 4)

self.assertEqual(iterSqrt(25), 5)

def testMathSqrt(self):

for i in range(0, 1001):

a=iterSqrt(i)

b=math.sqrt(i)

self.assertAlmostEqual(a, b, delta=0.001)

def testLessThan0(self):

self.assertIsNone(iterSqrt(-1))

def testIllegalStep(self):

self.assertRaises(IndexError, iterSqrt, 4, 0)

unittest.main()

eval exec

You can build Python Code dynamically and have it executed. The eval method will also return a value while the exec method only executes the code

myCode="math.pow((42 / 14), 2)"

exec(myCode)

res=eval(myCode)

By default the code have access to your current context (all variables you have access to). You can restrict it by defining your own context

myKontextLocal ={ "e" : 2.71828 }

exec(myCode, myKontextGlobal, myKontextLocal)

res=eval(myCode, myKontextGlobal, myKontextLocal)

Standard library

math

Math functions in Python

import cmath

math.e # 2.718281828459045

math.pi # 3.141592653589793

math.ceil(1.6) #2

math.floor(1.6) #1

math.ceil(-1.6) #-1

math.floor(-1.6) #-2

math.log10(1000) # 3

math.sqrt (9) # 3

math.sqrt (-1) # ValueError

cmath.sqrt(-1) # 1j

math.sin(math.pi/2) # 1

math.sin(math.radians(90)) # 1

Decimal

Exact float numbers

a=2.2

b=4.4

c=a+b # 6.6000000000000005

a=Dec("2.2")

b=Dec("4.4")

c=a+b # 6.6

Convert a Decimal into a String

You might want to get rid of trailing 0 behind the decimal point (42 instead of 42.000)

text=text.rstrip('0').rstrip('.')

Random

Random numbers in Python

random.seed()

r=random.randint(0,5) # 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5

r=random.choice(["a", "b", "c"]) # a,b or c

smp=random.sample(range(1,49+1), 6) # pick 6 numbers out of the range, e.g. [48, 26, 47, 34, 31, 6]

myList=(["a", "b", "c"])

random.shuffle(myList)

print(myList) # e.g. ['b', 'a', 'c']

Regular Expressions

Does this regular expression appear anywhere in the string?

res=re.search("[a-z]*", "Hello World")

if(res):

print("The regular expression "+str(res.re)+" found something in the string "+str(res.string))

Does this regular expression matches the start of the string?

if(not res):

print("No")

if(re.match("H[a-z]", "Hello World")):

print("Yes")

Use a regular expression more than once

if(stringWithNumber.match("Hello World") or stringWithNumber.match("Number1")):

Replace text with a regular expression

res=re.sub("[a-z]", "_", "Hello World") # H____ W____

If you put parts of your regular expressions in () you can use backreferences to access the hits in the replacements Do not forget to put r in front of the replacement string to protect to Example: You want to change the format of a date from mm/dd/yyyy to yyyy-mm-dd

You can also give readable names to your backreferences

Backreferences may even be used in the regular expression itself. Remove any character which is followed by the same character

Sometimes you want to replace text only if there is something special before or after the text. But you do not want to change what is arround your match. You just want to ensure it is there Example: Replace the word tea with coffee but only if it followed by a word starting with t You can either allow your regular expression to also match the extra word and copy it back via a backreference

Or you use (?=...) which is called a lookahead assertion

Hash

md5=hashlib.md5(b"Hello World").hexdigest()

Date and Time

res=datetime(year, month, day, hour, minute, sec)

now=datetime.now();

td=(now-res)

now=datetime.now().time()

int(now.strftime("%H"))

datetime.datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

Operating System Interaction

Interact with the OS your program is running on

os.environ # 'HOME': '/home/foo', ...

os.access("/home/tgunkel/my_files", os.X_OK) # True

for w in os.walk("/"):

print(w) # Current object, subfolder, files in folder

x=13123131414123123112

sys.getrefcount(x) # k

y=x

sys.getrefcount(x) # k+1

print(platform.machine()) #x86_64

Read command line arguments

pars=ArgumentParser()

pars.add_argument("-o", "--output", dest="outputfilename", default="out.txt")

pars.add_argument("-i", "--input", dest="inputfilename", default="in.txt")

#...

res=pars.parse_args()

print(res.outputfilename)

print(res.inputfilename)

This will autoamtically generate command line help for you

usage: tg1.py [-h] [-o OUTPUTFILENAME] [-i INPUTFILENAME]

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-o OUTPUTFILENAME, --output OUTPUTFILENAME

-i INPUTFILENAME, --input INPUTFILENAME

# python tg1.py -o a.txt -i b.txt

a.txt

b.txt

Python XML

class MyXMLHandler(sax.handler.ContentHandler):

def __init__(self):

pass

def startElement(self, name, attrs):

print("Start",name, sep=" ")

def endElement(self, name):

print("End",name, sep=" ")

def characters(self, content):

print("Content", content, sep=" ")

def endDocument(self):

print("End document")

h=MyXMLHandler()

p=sax.make_parser()

p.setContentHandler(h)

p.parse("/tmp/tg.xml")

Gettext

Have strings in your code translated for different languages. This a code example

gtt=gettext.translation("myTranslationFile", "extraStuff", languages=["de"])

gtt.install()

print(_("Good morning"))

print(_("Bye bye"))

The code uses Strings in English. The Strings are passed to the _("") method. We request the Strings to be translated to German ("de") and they should be found in the subfolder "extraStuff" and the file shall be called "myStranslationFile"

Every time you add or change a to be translated String issue

This will drop a file like this into the current folder where you can add your translations

msgid "Good morning"

msgstr "Guten Morgen"

#: YourCode.py:8

msgid "Bye bye"

msgstr "Auf Wiedersehen"

Once you are finished issue

and move the file into the subfolder where it is expected by Python

Now your code should display the translated lines

Guten Morgen

Auf Wiedersehen

SQL

con=sqlite3.connect(":memory:")

cur1=con.cursor()

cur1.execute("""CREATE TABLE testme (id INTEGER, name TEXT)""")

sql="""INSERT INTO testme (id,name) VALUES (:id, :name)"""

cur1.execute(sql, {"id":1, "name":"John"} )

cur1.execute(sql, {"id":2, "name":"Jane"} )

cur1.execute(sql, {"id":3, "name":"Frank"} )

cur1.execute("SELECT * from testme")

for row in cur1:

print(row)

Multithreading

Simple form of Multithreading in Python, but _thread in Python does not run faster on CPU with more than one core.

Start multiple threads

def checkPrime(k):

...

for i in range(0,100):

_thread.start_new(checkPrime, (i,))

Get a lock for critical sections

lockA.acquire()

...

lockA.release()

Object oriented approach for multithreading in Python

class PrimeChecker(threading.Thread):

def __init__(self, numberToCheck):

threading.Thread.__init__(self)

self.numberToCheck=numberToCheck

self.result=None

def run(self):

print("Started", self)

self.result=self.isPrime(self.numberToCheck)

print("Stopped", self)

def __str__(self):

return str(self.numberToCheck)+" "+str(self.result)

allMyThreads=list()

for i in range(0, 100000):

pc=PrimeChecker(i)

#pc.setDaemon(True)

pc.start()

allMyThreads.append(pc)

for t in allMyThreads:

t.join()

print(t)

Locking works similar

The Python module multiprocessing allows true parallel processing on more than one core. A small drawback is, that sharing data between such threads is a bit harder. You can either use special Queues

def checkPrime(k, results):

results.put([k, isPrime(k)])

if __name__== '__main__':

allMyThreads=list()

results = multiprocessing.Queue()

for i in range(0,1000):

p=multiprocessing.Process(target=checkPrime, args=(i,results))

allMyThreads.append(p)

p.start()

for p in allMyThreads:

p.join()

while not results.empty():

print(results.get())

or pipes

def inc(isServer, pipe):

if isServer:

for i in range(1,11):

pipe.send(i)

pipe.send("quit")

else:

while True:

res=pipe.recv()

print(res)

if("quit"==res):

break

if __name__== '__main__':

pipe1, pipe2 = multiprocessing.Pipe()

thread1=multiprocessing.Process(target=inc, args=(True, pipe1))

thread2=multiprocessing.Process(target=inc, args=(False, pipe2))

thread1.start()

thread2.start()

thread1.join()

thread2.join()

Network

Connect to localhost, Port 44444 to test this program

class MyRequestHandler(socketserver.BaseRequestHandler):

def handle(self):

clientAddr=self.client_address[0]

msg=self.request.recv(1024)

print("Got message:", msg, "from", clientAddr)

srv=socketserver.ThreadingTCPServer( ("", 44444), MyRequestHandler)

srv.serve_forever()

from email.mime.image import MIMEImage

from email.mime.multipart import MIMEMultipart

from email.mime.text import MIMEText

# Create the container (outer) email message.

msg = MIMEMultipart()

msg['Subject'] = 'Test Mail'

msg['From'] = "tgunkel@example.com"

msg['To'] = "tgunkel@example.com"

txt="Hallo Welt"

mtxt=MIMEText(txt.encode("utf-8"), _charset="utf-8")

msg.attach(mtxt)

fp = open("/tmp/picture.jpg", 'rb')

img = MIMEImage(fp.read())

fp.close()

msg.attach(img)

s = smtplib.SMTP('smtp_server.example.com')

s.send_message(msg)

s.quit()

Logging

'''

Configure the logging system, log to console plus to file

'''

# set log level for file an console

logLevelFile=logging.INFO

logLevelConsole=logging.DEBUG

# get root logger, all others will inherit its settings

rootLogger = logging.getLogger()

# set general log level to the minimum you did set for console and file (otherwise you will miss levels)

rootLogger.setLevel(min(logLevelFile, logLevelConsole))

# create file handler

filehandle = logging.FileHandler('root.log')

filehandle.setLevel(logLevelFile)

# create console handler

consolehandle = logging.StreamHandler()

consolehandle.setLevel(logLevelConsole)

# create formatter and add it to the handlers

formatter = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

filehandle.setFormatter(formatter)

consolehandle.setFormatter(formatter)

# add the handlers to the logger

rootLogger.addHandler(filehandle)

rootLogger.addHandler(consolehandle)

InitLogger()

logger=logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.info('Hallo Welt')

Profiling

Measure the total runtime of your methods

t1=timeit.Timer("iterSqrt(64)", "from __main__ import iterSqrt")

t2=timeit.Timer("sqrt(64)", "from math import sqrt")

numberOfTests=1000000

print(t1.timeit(numberOfTests))

print(t2.timeit(numberOfTests))

Get an overview which parts of your code need the most time

def myStartFunction():

...

cProfile.run("myStartFunction()")

Performance Advices

Use -O to compile your code. Will remove all assert instructions and __debug__ will be false.

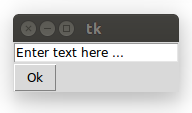

Python Graphical User Interface

One possible way to work with graphical user interfaces in Python is TkInter.

import tkinter

class MyFirstGUI(tkinter.Frame):

''' GUI class which extends the Frame class '''

def __init__(self, master=None):

tkinter.Frame.__init__(self, master)

self.pack()

self.addMyGUIelements()

def addMyGUIelements(self):

# A text input field

self.giveMeYourText=tkinter.Entry(self)

self.giveMeYourText.pack()

self.yourTextGoesHere=tkinter.StringVar()

self.yourTextGoesHere.set("Enter text here ...")

self.giveMeYourText["textvariable"]=self.yourTextGoesHere

# ok button

self.ok=tkinter.Button(self)

self.ok["text"]="Ok"

self.ok["command"]=self.doSomething # is is only the name of the method to call, so no parameters!

self.ok.pack(side="left")

def doSomething(self):

print(self.giveMeYourText.get())

self.quit()

m=MyFirstGUI(tkinter.Tk())

m.mainloop()

Distribution of Python Programs

Create a file called setup.py in the toplevel folder of you project like this

setup(name="MyFirstPythonProgram",

version="0.9",

author="Jon Doe",

author_email="john@example.com",

url="http://www.tgunkel.de",

scripts=["start_it.sh"],

#py_modules=["de.tgunkel.pythondemo.Demo1", "de.tgunkel.pythondemo.demo"]

packages=["de.tgunkel", "de.tgunkel.pythondemo"]

)

List either all modules (the files with your Python code) or all packages (the subfolders of the src folder where you Python code is in) You can also add scripts at the top level of your project and have them installed for you later on.

Call the setup.py program like this

python setup.py bdist_wininst

python setup.py bdist_rpm

The users can install the packages like this

Python and Excel Files

Reading XLS files

Download xlrd extract it and install it

Small example how to read an XLS / Excel file in Python

wb = xlrd.open_workbook(self.importFile)

worksheet = wb.sheet_by_index(0)

num_rows = worksheet.nrows - 1

num_cells = worksheet.ncols - 1

curr_row = -1

resultRows=[]

while curr_row < num_rows:

curr_row += 1

#row = worksheet.row(curr_row)

curr_cell = -1

resultCols=[]

while (curr_cell < num_cells):

curr_cell += 1

# Cell Types: 0=Empty, 1=Text, 2=Number, 3=Date, 4=Boolean, 5=Error, 6=Blank

cell_type = worksheet.cell_type(curr_row, curr_cell)

cell_value = worksheet.cell_value(curr_row, curr_cell)

# depending on the cell type, store the value slightly different

if(xlrd.XL_CELL_EMPTY==cell_type):

resultCols.append(None)

elif(xlrd.XL_CELL_TEXT==cell_type):

resultCols.append(cell_value)

elif(xlrd.XL_CELL_NUMBER==cell_type):

# get rid of the e+ notation

num_val=str(Decimal(cell_value))

resultCols.append(num_val)

elif(xlrd.XL_CELL_DATE==str(cell_type)):

resultCols.append(cell_value)

else:

resultCols.append(str(cell_value))

resultRows.append(resultCols)

return resultRows

Create / Write Excel files

XLSXWriter can be downloaded here. Install it

Example how to write with Python and XLSX / Excel file

from datetime import datetime

workbook = xlsxwriter.Workbook('c:temphello.xlsx')

worksheet = workbook.add_worksheet()

worksheet.write('A1', 'Hello world')

worksheet.write(0, 1, 'Hello moon')

date_format = workbook.add_format({'num_format': 'dd/mm/yyyy', 'align': 'left'})

number_format = workbook.add_format({'num_format': '0', 'align': 'right'})

number_format_4 = workbook.add_format({'num_format': '0.0000', 'align': 'right'})

text_format = workbook.add_format({'num_format': '@', 'align': 'left'})

my_date = datetime.strptime('2014-02-07', '%Y-%m-%d')

worksheet.write_datetime(0, 2, my_date, date_format)

worksheet.write_string(0, 3, “Hello again”, text_format)

worksheet.write_number(0, 4, Decimal(“42.0”), number_format_4)

worksheet.write_blank(1, 0, '')

workbook.close()